What is money?

It's subjective

Money is gold, and nothing else.

Money is something completely necessary in our society, and most people come in contact with money every day. We might use it to buy things, worry about our expenses, that we don’t have enough, or even be glad for how much we have. But we seldom stop and think of what money really is.

Not just how the physical coins and pieces of paper are made, but why does money exist? What makes it valuable? Are there different kinds of money? And are some forms of money better than others?

Before getting interested in cryptocurrencies I too had never asked these questions and with this chapter, I hope to provide some insight into this admittedly complex topic.

Historical examples of money

First, let’s look at some interesting historical examples of items that have been used as money. Some are quite fascinating.

Shells

Sea shells have been used as money for centuries and were commonly used in parts of Africa and Asia but also in other parts of the world. In West Africa, they saw significant use until the 20th century.

Coins in ancient Greece

The Greeks used coins made from precious metal like silver, bronze, and gold. They also stamped the coins with beautiful portraits for a truly modern look.

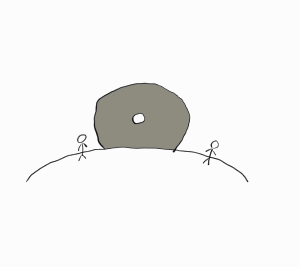

Rai stones

Rai stones is a form of stone money on the Yap Islands. They can be up to 4 m in diameter but most are much smaller, down to around 3.5 cm in diameter. Instead of moving the big ones, you simply tell people you’ve transferred them, like a social ledger. Here are some great pictures.

A 20kg copper coin

Another example of—let’s say interesting—form of money is the world’s largest coin. It’s a copper coin weighing 20kg, issued in Sweden.

Since copper was worth much less than silver, very large coins had to be made to offset the difference. At that time, coins did contain raw materials according to their value, which isn’t the case today.

A 100 billion mark note

Bank notes—paper money—are easy to use but they do have problems of their own. Unless kept in check, by for example the gold standard, they can be mass produced to cause hyperinflation.

This is what happened in Germany after the first World War. They had massive debts after losing the war, so they tried to print enough money to pay off the debts.

While the inflation was slow at first it quickly ramped up. It culminated in 1924 with a 100 billion mark note, while only four years earlier 100 mark notes were used.

Cigarettes in prison

Like depicted in the movie Shawshank Redemption cigarettes are used in some prisons as a form of money. Today, some prisons have started to ban smoking, so they instead use things like stamps or ramen.

Euro bank notes

There are many kinds of fiat currencies, for example, the Euro. Modern coins aren’t made of valuable metal and paper notes are used for large denominations.

Dogecoin

Dogecoin is a cryptocurrency and while created as a “joke currency” it quickly gained popularity as a tipping tool online. You can still find merchants who accept it today for things like domain names, web hosting, VPNs, or games.

Marbles on the school yard

Kids on the school-yard often come up with interesting forms of money. For example, collectible card games or game components. Another example is marbles used in a Swedish game where you win your opponents marbles. (And those with many marbles had higher status in class.)

The gold standard

There’s an important historical point to make about fiat. First used 1821 in the United Kingdom, the gold standard made sure to back each currency unit with gold. So if you had 1,000 bank notes, you could exchange them for a specific weight in gold bullion. This was used in various ways up until 1971, when it was finally abandoned completely.

Bartering, and why do we need money?

What would life look like if we didn’t have money? We would have to turn to bartering—trading goods or services directly.

But there are problems with this system:

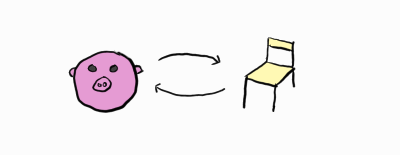

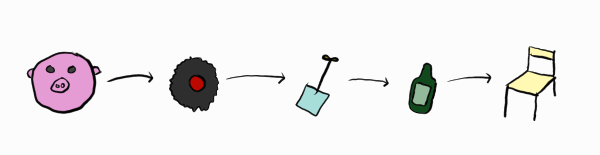

What if the carpenter doesn’t want your pig?

You would have to trade with others and find something the seller would accept.

It can sometimes be very cumbersome to trade for something the carpenter wants—in this case a bottle of rum. Each step in the process needs a matching buyer and seller. What if you want to buy a loaf of bread, worth much less than a single pig?

You would have to kill a pig and offer parts to him. It’s undesirable if the pig hasn’t grown up yet and you’ll get stuck with leftover parts.

In short, it’s extremely inefficient.

This is why we as a society prefer to use money. Even if the thing we use as money itself is basically worthless—like pieces of paper—the function it serves is very valuable.

State theory of money

One common answer to the question “what gives money value?” is the State Theory of Money (many refer to it unknowingly).

The basic thesis is that it’s the state that gives value to money:

Fiat currency is declared by the state to be legal tender.

Which, among other things, means merchants have to accept it by law.

- The state is responsible to regulate inflation.

- Banks are insured by the state, increasing safety of the currency.

- During the gold standard the state ensured that fiat currencies were backed by gold.

While this might on the surface explain why fiat currencies are valuable, it fails to explain why other forms of money become valuable.

Subjective theory of value

Instead, a better explanation is given by the subjective theory of value. It describes how goods are valued, but it serves just as well to explain why money is valuable.

In short, it says that value is subjective.

It might sound too simplistic or like a tautology. But what it means is there’s no global deciding function that gives value. Instead, each person independently assigns value.

For instance, medicine can be extremely valuable for those who need it, but could have little value to others. So if you have the medicine, but don’t need it, you’ll gladly sell. But someone who needs it would be reluctant to sell, unless it’s for a very high price.

What does it mean for money? That the value of money is emergent from a group of individuals. If, for example, everyone in your social group declare that tomorrow they’ll use Pokémon trading cards as money, then the trading cards suddenly become very valuable to you. The more people that use a form of money, the better it works and the more value it will have.

States don’t give money value, but they can contribute. For example, declaring fiat legal tender makes more people accept it, which in turn increases its value.

What functions does money serve?

If anything can be used as money, it makes more sense to look at how money is used. Knowledgeable people seem to agree money has three major functions:

Medium of exchange

It can be used to intermediate the exchange of goods and services.

For example, the use of sea shells as money. The shells themselves aren’t particularly useful, but their use as a medium of exchange is.

Unit of account

A standard unit to measure the market value of goods and services.

For instance, car prices across Sweden can be compared in SEK.

Store of value

It maintains its value over time.

A piece of gold could, for example, buy clothes in both ancient Greece and today.

Medium of exchange is the most important defining property of money, the other properties follow.

Note that these are functions of usage and adoption. For instance, if something has been a store of value for a period of time, it doesn’t mean it will continue to be a good store of value in the future.

Now we may wonder, can anything be used as money? And are there “good” and “bad” forms of money?

As seen from historical examples, I think it’s safe to conclude that yes, basically anything can be used as money. But if we want to compare how well different forms of money work, we need to look at other properties.

What properties does good money have?

To function as money, money should have these properties:

Acceptable

Everyone must be able to use the money for transactions.

If only the very rich can use it, then it’s not good money.

Divisible

Can be divided into smaller units of value.

If it’s difficult to subdivide, then it’s hard to use in practice. It’s why cash always come with coins and notes with different values.

Durable

An item must be able to withstand repeated use.

Food is not durable and makes for poor money.

Fungible & Uniform

Two items of the same type should always be considered equal.

All shares in a company should be worth the same, even if bought at different times and at different prices. All gold coins of the same denomination should contain the same amount of gold.

Limited in supply

There should be a limited and predictable amount of money.

A limited amount is needed for the money to hold its value.

Portable

It’s easy to carry around money and to transfer it to others.

Money should be practical.

Recognizable

Money should be easy to identify and difficult to counterfeit.

You should be able to differentiate between different types of money, so you don’t mistake Dollar notes for Euro or Monopoly notes, and you should be able to separate real from fake notes. This is sometimes referred to as cognizable.

We can summarize the properties as: money should be practical and efficient.

It makes sense as the point of money is to increase efficiency. If money isn’t practical, it’s not a good medium of exchange.

How well do our historical examples work as money?

How do our historical examples of money hold up? They don’t include examples of outright bad forms1, but some are indeed better than others.

The large Rai stones and the 20kg copper coin are great examples of money that isn’t portable. Therefore, they don’t work very well as money.2

Cigarettes, marbles, stamps and other types of commodities are decent forms of money—on a small scale. They have some durability issues (wear and tear) and they’re not perfectly uniform. But most importantly, they can be mass produced which prevents their use on a larger scale.3

Sea shells work well as money—assuming they’re not too plentiful. If used in a local market—for example on an island—there’s always a risk of the market being overrun by shells from other islands, where they’re more common. But they’re durable, lightweight and easy to use, which are great properties for money to have.

Metal coins is a very good form of money, especially if made by scarce material. Gold is naturally very scarce, ensuring a limited supply, and coins are easy to use and very durable. This is the reason coins have been the dominating type of currency for over 2000 years.

How well cryptocurrencies work as money is a topic for the next chapter.

The problem with fiat currencies

The money we usually use today is a little different from coins made of precious materials. We use coins made with cheap metal or paper notes, and our money is often just stored digitally at a bank. After abandoning the gold standard, there’s nothing physically backing up the value of money.

It’s not a requirement that the money must be backed by something, or have intrinsic value like commodity money. The real problem is that the supply isn’t limited. Banks inflate the supply using fractional banking while central banks can print money, both physical and digital, without any limit.

The term sound money refers to money that isn’t prone to sudden changes in long term purchasing power, and the value is determined by the free market. If the supply of money differs from the demand, which will happen with fiat due to the disconnect between banks and the market, then there might be sudden changes to the purchasing power.

While fiat has many positive properties, after the move away from the gold standard, it’s now considered unsound money.

Why do we need good money?

Outside of curiosity, why does it matter if there are better forms of money? If fiat is good enough, why bother?

I see two major reasons:

The point of money is to increase economic efficiency.

Better forms of money are more efficient.

Money with poor properties can lead to large economic problems.

For instance how the ability to print fiat money from thin air can lead to hyperinflation.

In our context, knowing what makes money perform well helps us reason about cryptocurrencies, and to see if they can live up to their namesake.