Improved voting

A verifiable and resilient voting system

Nobody is in favor of the power going down. Nobody is in favor of all cell phones not working. But an election? There are sides. Half of the country will want the result to stand and half the country will want the result overturned; they’ll decide on their course of action based on the result, not based on what’s right.

In this chapter, we’ll look at some of the problems with the way we vote and how we might use cryptocurrencies (or “the blockchain”) to make an improved voting scheme.

I say they might help because it’s not a use-case where I know they will provide value; it’s still unclear how much benefit it would bring and blockchain voting may even be a fundamentally bad idea. But as I’ll argue, there are some very good properties it can provide, so the idea isn’t so bad it can be thrown out directly.

Bush v. Gore

But why do we talk about improving voting? What’s the problem with the way we vote? Hasn’t voting on paper and having people count them worked great for us so far?

Firstly, we shouldn’t avoid looking for improvements just because the “old way” worked well. If so then we wouldn’t have faster cars, bigger TV-screens or more effective medicine—the previous versions already worked well enough. There’s always value in making something better.

But there are also serious problems with our voting system. A great example of some of them is the United States presidential election of 2000, where George W. Bush edged out Al Gore in a historically close election—at least according to Britannica, which I use as a source for the events.

To say that the election was close does it a disservice. After a day full of uncertainty, where Gore had called Bush to concede the election just to withdraw it later, it was clear Florida would be the decider. Bush appeared to have won in Florida with a margin of roughly 0.01%—a couple of hundred votes out of six million votes. This was so close that a machine recount was made, which showed that Bush had indeed won with only 327 votes!

Here we need to realize that the machines aren’t computers that just count the votes digitally. They’re machines that take the ballots, examines them and tries to figure out what vote is marked (or punched) on the ballot.

The problem here is that some of the ballots weren’t in good condition. Some ballots weren’t punched through completely (so the machines couldn’t detect the votes), others had voted for the same office multiple times or were incomplete in other ways. With the election being so close it’s easy to see that these votes could very well change the outcome. Therefore the Florida Supreme Court ruled that these questionable ballots should be recounted by hand.

Because the stakes were fairly high (an understatement I know) there was a ton of legal action, and charges of conflict of interest were pushed by both parties. At the end the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the Florida decision and put a stop to the recounting, awarded Florida’s votes to Bush and that no recount could be held in time.

So in the end the Supreme Court decided to end the election and might have changed the outcome in the process. That’s a pretty big failure of the voting system right there.

The problems with paper voting

One of the issues with the U.S. election is that there are essentially only two parties and the winner of the election takes it all. Therefore such a small difference as a couple of hundred votes did have a huge impact. If Al Gore had won, our world might have looked completely different today.

But we also saw some problems that are caused by using paper votes:

Inexact vote counting

Humans counting votes will inevitably have a margin of error, but so will these voting machines that cannot see what we humans can.

Counting votes is slow

Counting, and recounting, can take weeks and at the end of the 2000 U.S. presidential election it would supposedly take too long so the human recount was skipped.

Invalid ballots

What if you accidentally leave a mark on an unintended place on your vote? Or if you don’t leave a big enough mark? Now your vote might not count.

Corruption

Why was a human recount ordered and why was it thrown out? Who decides if a questionable ballot is invalid or not? These are all human decisions that are vulnerable to corruption (or incompetence).

The problems with electronic voting

In order to address some of the problems with paper voting, electronic voting is growing in popularity. The benefits are clear; you avoid the problem with questionable ballots and vote counting is precise and instant. But there are significant drawbacks that make them a very bad idea:

Lack of transparency

How do you know that your vote has been counted correctly? That the machine didn’t switch it out for some other vote? An electronic voting machine is largely a black box, one we’re not sure how it works so we just hope it does the right thing.

Hacking

It’s much easier to hack electronic voting machines—to change votes from Clinton to Trump for example—than to hack paper voting. With paper voting you’d have to have people on site to exchange paper votes for new paper votes, but hacking a computer can be done from the other side of the world.

Corruption

In the same way hacking is a worry, so is corruption. If you want to influence votes all you’d have to do is switch out or reprogram the voting machine, and after that nobody would notice. With paper voting it’s harder since there are many more constantly watching what happens to the votes, so you’d have to bribe more people to get away with it.

Privacy concerns

Paper voting preserves your privacy very well. You walk behind a screen, select a paper and put it a box with hundreds of other papers, making it basically impossible to trace that one vote back to you. Simple and very effective.

Not so with electronic voting. The voting machine needs to verify your identity some way and computers can—and therefore we must assume they will—record everything that happens on it. This is information that a hacker or election worker could gain access to, and would be able to see exactly who you voted for.

Consider for example what would happen if the future government becomes corrupt. Like if a Nazi-like party comes to power and they decide to punish those who didn’t vote for them in the election?

Understandability

It’s easy to explain how paper voting works; you just count the pieces of paper and tally up which name occurs the most. It’s much more difficult to explain how electronic voting works and what makes it trustworthy.

How does it for example prevent someone from voting twice? With paper voting there are people who check that you’re only placing a single vote in the box, but how does the computer do that? How do you know the computer counted your vote correctly? And how will the election worker know that connecting a USB memory stick into the voting machine opens it up for attacks?

This is a general problem with technology, as people are often too trusting of them. We think they always do the right thing, but we underestimate the risk for faults or vulnerabilities in them. Just take self-driving cars as an example; they’re still very much unsafe—both for passangers and pedestrians—but people don’t seem to realize it.

Understandability is important because people have to trust their election to be fair. If they don’t trust their votes being counted correctly, then they can’t trust the outcome of the election either.

For a convincing case against electronic voting, I recommend Jennifer Cohn’s article America’s Electronic Voting System is Corrupted to the Core.

On the other hand many of these problems can be mitigated, see the paper Public Evidence from Secret Ballots for a good rundown.

A blockchain voting system

As an alternative I’ll try to present a high level description of a blockchain voting scheme, which have some very good and beneficial properties:

Transparent

The system is public so anyone can verify that it works like it’s supposed to, which obstructs corruption and hacking. There’s still trust here, trust that someone will audit the scheme, but it’s a big step up from other black box voting systems where nobody can tell what’s going on.

Verifiable

Anyone can verify the integrity of the voting result. It can with certainty answer questions like:

- Did my vote get counted?

- Did it get counted correctly?

- How many votes were given out in total?

- How many votes were cast?

- What was the outcome?

If you happened to use a corrupt voting machine that changed your vote from Hillary to Trump, you could use another device and see that’s what happened. You can also be sure that your vote was counted correctly, or if you didn’t vote that it wasn’t included and you can verify yourself that all votes were tallied correctly. In this scheme vote counting is alway verifiably correct.

No questionable votes

The system will automatically reject invalid votes, so you cannot send a vote voting for multiple candidates for example. Either your vote is valid or it’s not, which you can always verify when you vote. (Practically this would be done automatically by whatever voting program you use, radically reducing the risk for errors.)

Instant vote counting

Because it’s a form of electronic voting, votes can be counted instantly and you get real-time updates as the votes come in.

Vote anywhere

It’s possible to set it up so you can vote with your mobile phone, from the other side of the world. This would allow for direct democracy where people can vote on policy directly, with very minor overhead.

Harder to disrupt

Because the system only relies on a central party for the initial vote setup, and after that the voting is carried out by independent nodes in the network, it’s more resilient against disruptions than a centralized scheme.

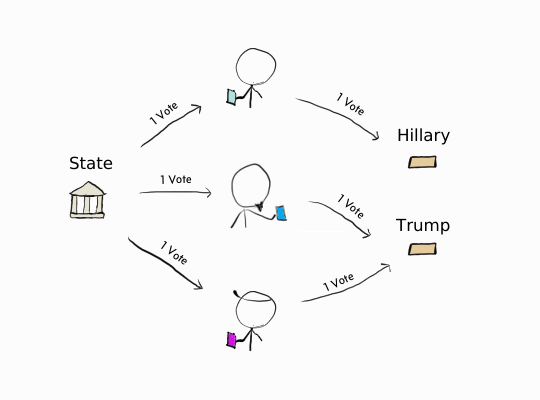

The scheme is similar to tokens that we discussed in the previous chapter. Here the issuer is the government, who still needs a way to identify voters and to give them a token (a single vote). The process would be similar to how it works today, where people have their identification verified by voting officials when they go to vote.1

With the tokens distributed, you could cast a vote by sending them to predetermined addresses to cast your vote. For example if you want to vote for Trump, you send it to the Trump address. If you want to vote for Hillary, you send it to the Hillary address. And if you don’t want to vote you don’t do anything.2

These transactions work like cryptocurrency transactions, so you cannot counterfeit them or manufacture votes from thin air. Well, the state could issue new votes, but everyone can see exactly how many votes they give out, so if they give out more votes than eligible voters in the country… You know something is wrong.3

It’s easy to count the votes—just check how much each address holds. It’s also easy for you to see that your vote has arrived to the correct voting address, and if it did you know your vote will count.

Unsolved problems

The scheme I’ve presented is simple—too simple. There are many problems with it, some that are solvable but others that I don’t have an answer to.

Privacy

The big flaw is the poor privacy. If you can connect token issuance with your identification—which the government will be able to do—then they can see who you voted for. It has the same privacy problem that Bitcoin has, except it’s even worse as there’s always a direct link between you and your address.

The solution would be to obscure the coin history between issuance of the token and when you cast your vote. We could use the obfuscation techniques, described in the privacy and fungibility part of the appendix, to accomplish this.

It’s important to note that the privacy scheme has very high requirements. It’s not enough that it seems to be good today, it has to hold up in 10, 20 or maybe even 100 years from now.

Key delivery

This whole scheme rests on the ability and the trust that the state can somehow distribute votes fairly and correctly. I don’t think the trust issue is different from how it works today, but there many details on how votes are distributed that needs to be ironed out.

I do think it’s a problem that can be solved. For example in Sweden we have BankID, an electronic citizen identification solution, that we use to file our taxes, login to banks and many other things. It’s really like an electronic identification card that could in theory be used to authenticate electronic votes as well.

Stealing votes

While the system itself could of course be hacked (anything could theoretically be broken), I see stealing individual votes as a bigger problem. For example if voting should be carried out on mobile phones, what if some malware has infected your phone and decides to change your vote? Or if a hacker can hack the voting app you use?

One possible solution might be for people to change their votes before the voting is over, so they could verify their vote on another phone or computer, and do something about it if something has gone wrong. But this is problematic in other ways, like allowing you to change your vote if you see the vote isn’t going your way.

Vote buying

Another concern is that it might make buying and selling votes easier. With paper voting there’s no easy way to prove you voted one way (other than bringing a camera with you and record your actions).

But with this scheme you can with 100% certainty prove who you voted for. If you wanted to you could also give your vote to someone else, or they might try to coerce you to do so.

Understandability

If electronic voting was hard for people to understand and accept, this wouldn’t be any easier. If anything “blockchain voting” is even harder to understand, especially as many technologically proficient people still regard the blockchain as a panacea that can solve any problem.

Why a blockchain?

The big question to ask is why would we want voting on a blockchain anyway? Why would we want to record our votes on a permanent database, when we might even want to allow people to change their votes before the voting is over? Why design a voting a scheme on an extremely inefficient system—that all cryptocurrencies and blockchain applications are?

As pointed out in the paper Public Evidence from Secret Ballots it’s possible to create an end-to-end verifiable electronic voting scheme even without the blockchain—which isn’t surprising since the blockchain is just a database. They also say that because we already trust a central entity to give out the voting privileges, we can just trust them to publish a ledger of the events, making the blockchain obsolete.

They say a lot of other things too, and I recommend you read the paper as it goes through a lot of the difficulties and possible solutions with voting systems. It’s not as simple as I may have led you to believe.

They’re right that trust isn’t an issue, since data will be independently verified for correctness anyway, but I don’t agree that it makes a blockchain useless. A fault tolerant system—such as a blockchain—is inherently more difficult to disrupt. Because anyone can help collect, distribute and verify votes it doesn’t matter if the government’s servers gets overloaded in a Denial of Service (DoS) attack—as long as people have internet access the voting process will be uninterrupted.

While there are benefits to blockchain voting, there are many problems we need to solve first, with the privacy problem being the most important. And it’s possible that when all things are considered, maybe paper voting is best after all.